Period: 1428–1521 CE

Founders: Triple Alliance (Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tlacopan)

Capital: Tenochtitlan

Peak Population: ~5 million (c. 1519)

Legacy: Chinampa agriculture, monumental architecture, complex calendrical systems

- Introduction

- Origins and Early History

- Expansion and Military Structure

- Administrative and Tribute Innovations

- Economic Foundations

- Architectural and Cultural Achievements

- Science, Medicine and Technology

- Religion, Education and Intellectual Currents

- Diplomacy and Regional Alliances

- Society and Daily Life

- Women and Gender Roles

- Art, Literature and Intellectual Exchange

- Music and Performing Arts

- Cuisine and Culinary Traditions

- Infrastructure and Urban Planning

- Tribute System and Provincial Elites

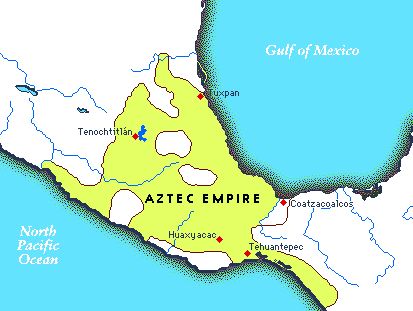

- Imperial Cartography and Geography

- Challenges, Conflicts and Decline

- Conclusion

Introduction

The Aztec Empire, centered on the island city of Tenochtitlan in Lake Texcoco, rose between 1428 and 1521 CE to dominate large parts of central Mexico. Built as a triple alliance among Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan, it united diverse city-states under a hegemonic rulers. At its height, it ruled over approximately five million people through a combination of military conquest, tribute administration and religious legitimation. The Aztecs engineered floating gardens, built monumental pyramids and developed complex calendrical and writing systems. Their society blended warfare, ritual and commerce into an urbanized imperial structure that impressed both contemporary Mesoamericans and later European visitors.

Origins and Early History (12th–15th centuries)

The Mexica people, migrating from Aztlan, arrived in the Valley of Mexico in the late 13th century. After initial subordination to established city-states, they founded Tenochtitlan in 1325 on a swampy island. Over the next century they forged military and matrimonial alliances with Texcoco and Tlacopan, culminating in the formation of the Triple Alliance in 1428. Under leaders like Itzcoatl and Moctezuma I, the Mexica overthrew Tepanec overlords and began aggressive expansion, establishing the framework for imperial rule.

Expansion and Military Structure

Aztec armies comprised professional warriors drawn from noble ranks, including Jaguar and Eagle knights, and conscripted commoners. They employed obsidian macuahuitl swords, atlatl darts and siege tactics against fortified towns. Conquests from the Basin of Mexico to the Gulf Coast and Oaxaca were followed by garrison placement and tribute demands. Seasonal campaigns combined religious ceremonies—capturing prisoners for sacrifice—with territorial subjugation.

Administrative and Tribute Innovations

The emperor (tlatoani) presided over a hierarchy of nobles, judges (teuctin), governors (tlacochcalcatl) and magistrates. Provinces (altepetl) retained local rulers under Aztec supervision. A central tribute system catalogued goods—cacao, cotton, maize, animal skins—delivered annually to Tenochtitlan’s warehouses. Tribute records and pictorial codices ensured accountability and financed the court, temples and military.

Economic Foundations

The Aztec economy blended intensive agriculture—chinampa raised beds on lake shallows producing multiple harvests per year—with long-distance trade conducted by pochteca merchants. Markets like Tlatelolco traded local produce, luxury feathers, cacao and slaves. State-controlled marketplaces operated under strict regulations enforced by officials (pochteca grande).

Architectural and Cultural Achievements

Tenochtitlan’s urban core featured two giant pyramids to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, the Templo Mayor, and palaces with intricately carved stone facades. Aqueducts supplied fresh water; causeways with retractable bridges linked the island to the mainland. Monumental sculpture, stucco reliefs and colourful murals adorned public spaces.

Science, Medicine and Technology

Aztec scholars recorded eclipses and planetary cycles in pictorial codices, using a 365-day xiuhpohualli and 260-day tonalpohualli calendars. Herbalists compiled extensive pharmacopoeias for treating fevers, wounds and snakebites. Engineering feats included chinampa drainage, causeway construction and aqueduct maintenance.

Religion, Education and Intellectual Currents

State religion centered on the worship of sun and rain deities—Huitzilopochtli, Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl. Massive human sacrifices at temple tops reinforced imperial ideology. Calmecac schools educated noble youth in theology, history, poetry and military arts, while Telpochcalli taught commoners warfare, song and craft.

Diplomacy and Regional Alliances

The Triple Alliance maintained tributary relationships with over eighty city-states. Diplomatic envoys secured trade privileges and managed succession disputes. Marital alliances between noble families integrated local elites into the imperial network, ensuring loyalty and cultural exchange.

Society and Daily Life

Commoners lived in household compounds (calpulli), working chinampas or as artisans in guild-like calpulli workshops. Daily life revolved around communal feasts, pulque consumption and market attendance. Clothing indicated status—noble tilmatli cloaks and cotton garments versus maguey fiber tunics for commoners.

Women and Gender Roles

Noble women influenced politics through family networks and could hold land rights. Priestesses served in major temples. Most women managed households, wove cotton cloth and prepared food staples like tamales and tortillas. Some commoner women sold produce in markets.

Art, Literature and Intellectual Exchange

Aztec poets composed hymns and philosophical verses in Nahuatl, collected by Spanish friars in Florentine Codex. Eagle and puma cloaks, featherwork headdresses and richly painted codices exemplify indigenous artistry. Interaction with Mixtec and Maya traditions enriched local iconography.

Music and Performing Arts

Musical performance incorporated flutes (ocarina, teponaztli drums) and percussion (huehuetl). Ceremonial dances—xochipilli and volador rituals—blended spiritual devotion with martial display.

Cuisine and Culinary Traditions

Staple foods included maize tamales, atole gruel and tortillas. Chinampa gardens produced chilies, tomatoes, squash and amaranth. Gourmet dishes featured turkey, duck, insects and chocolate beverages seasoned with vanilla and chilies.

Infrastructure and Urban Planning

Tenochtitlan’s grid layout integrated sacred precinct, palaces and dense residential zones. Causeways, canals and aqueducts enabled transport and water supply. Chinampa networks extended arable land into the lake basin.

Tribute System and Provincial Elites

Provincial rulers (tlatoani of tributary altepetl) collected local tribute in kind and forwarded quotas. Successful tribute collectors advanced in noble rank and could secure positions at Tenochtitlan’s court, blending local authority with imperial hierarchy.

Imperial Cartography and Geography

Aztec mapmakers produced pictorial maps (tlacuilolli) showing tribute districts, waterways and pilgrimage routes. These Ñantzin codices guided tax collection, military campaigns and religious festivals.

Challenges, Conflicts and Decline

Continuous warfare against Tlaxcala, Cholula and Purépecha drained resources. Smallpox epidemic (1520) decimated population. In 1519 Hernán Cortés formed alliances with subject city-states and, after a brutal siege in 1521, toppled Tenochtitlan, ending the empire.

Conclusion

The Aztec Empire’s innovations in agriculture, urbanism, art and governance left a lasting imprint on central Mexico. Its monumental ruins, codices and linguistic heritage endure, providing insights into a civilization that balanced martial vigour, ritual devotion and cosmopolitan culture at the heart of Mesoamerica.

Additional Resources and Further Reading

- "The Aztecs" – Michael E. Smith

- "Aztec Thought and Culture" – Miguel León-Portilla

- "Daily Life of the Aztecs" – David Carrasco

- "The Aztec World" – Elizabeth M. Brumfiel and Gary M. Feinman

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Aztec Empire?

The Aztec Empire was a powerful Mesoamerican alliance ruled from Tenochtitlan between 1428 and 1521, noted for its military prowess and ritual culture.

Why is the Aztec Empire significant?

It pioneered chinampa agriculture, built monumental pyramids, developed a rich codex tradition and shaped the cultural landscape of central Mexico.