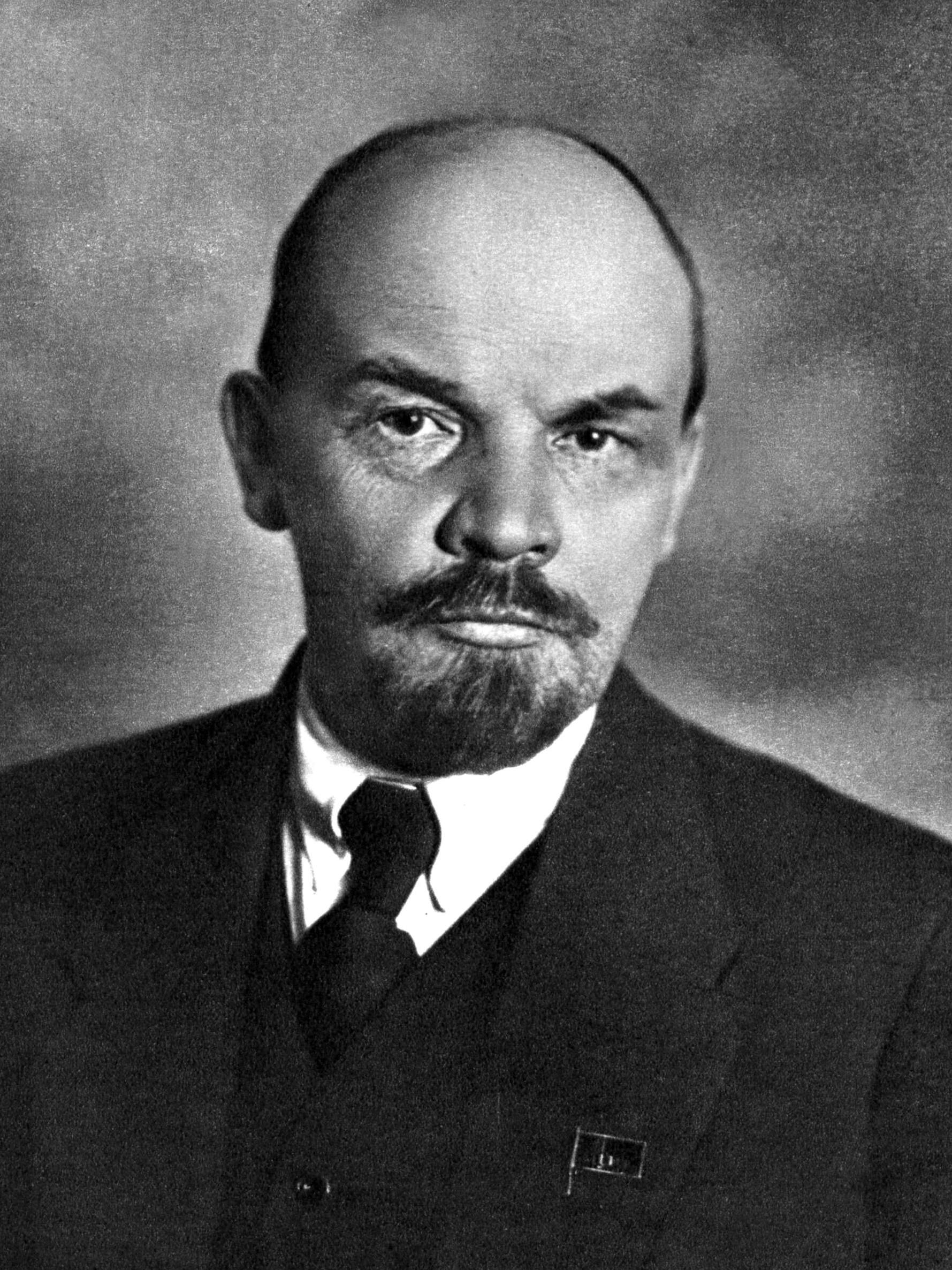

📚 Lenin Biography in English

This page provides comprehensive information about Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known as Lenin (1870-1924). Lenin was the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution and founder of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics who established the theory of Marxism-Leninism. This content is prepared based on reliable historical sources and historical documents.

Full Name: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov

Birth: April 22, 1870

Death: January 21, 1924

Nationality: Russian

Occupation: Revolutionary, Politician, Theorist

Famous for: Leader of Bolshevik Revolution

Spouse: Nadezhda Krupskaya

👶 Early Life and Revolutionary Character Formation

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born on April 22, 1870, in the city of Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk) into a middle-class, educated family. His father, Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov, was a school inspector for the region and held the hereditary noble rank, while his mother, Maria Alexandrovna Blank, came from an intellectual family with German and Swedish ancestry. This family environment, filled with values of education, justice, and criticism of the Tsarist autocratic system, played a decisive role in shaping Lenin's revolutionary character.

The Ulyanov household was marked by intellectual discourse and progressive thinking. Lenin's father was dedicated to expanding educational opportunities for peasants and minorities, often clashing with conservative bureaucrats. This early exposure to social justice issues and his father's commitment to improving conditions for the oppressed deeply influenced young Vladimir's worldview. The family owned a modest estate and employed servants, giving Lenin firsthand knowledge of class distinctions that would later inform his revolutionary theory.

The defining event of Lenin's life was the execution of his older brother Alexander in 1887 for participating in a conspiracy to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. Alexander, a student at St. Petersburg University, had become involved with the revolutionary group "People's Will" and was caught carrying a bomb intended for the Tsar. This bitter event not only plunged the Ulyanov family into grief and social ostracism but also caused a deep political awakening in young Lenin. He learned from this painful experience that individual struggle and terrorism against Tsarist autocracy was not enough; there was a need for mass organization and organized revolution.

Following his brother's execution, Lenin was expelled from Kazan University for participating in student protests. He was forced to continue his legal studies independently, demonstrating remarkable intellectual discipline by completing his law degree in just one year as an external student at St. Petersburg University. During this period of forced isolation, he voraciously read the works of revolutionary thinkers, particularly Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, whose ideas would fundamentally shape his political philosophy.

🎓 Intellectual Development and Legal Career

Despite his revolutionary leanings, Lenin briefly practiced law in Samara, where he gained intimate knowledge of the Russian legal system and its inherent injustices. His legal practice primarily involved defending peasants and workers against wealthy landowners and factory owners, experiences that reinforced his belief in the fundamental inequality of the capitalist system. He observed firsthand how the law served the interests of the ruling class while oppressing the working masses.

During his time in Samara, Lenin also witnessed the devastating famine of 1891-92, which killed hundreds of thousands of peasants while the government and wealthy classes remained largely indifferent. This catastrophe further radicalized him, convincing him that only revolutionary change could address Russia's systemic problems. He began to see famine, poverty, and oppression not as natural disasters but as inevitable consequences of an unjust social system.

🔥 Revolutionary Activities and Marxist Development (1893-1900)

In 1893, Lenin moved to St. Petersburg, where he became deeply involved in Marxist circles and revolutionary activities. He joined various underground groups studying Marx's "Capital" and began developing his own interpretations of Marxist theory as applied to Russian conditions. Unlike many contemporary revolutionaries who focused on peasant uprisings, Lenin became convinced that the industrial working class (proletariat) would be the driving force of revolution in Russia.

Lenin's first major theoretical work, "What the 'Friends of the People' Are and How They Fight the Social-Democrats" (1894), established him as a formidable Marxist theorist. In this work, he criticized the Populist movement, which idealized peasant life and believed Russia could skip the capitalist stage of development. Lenin argued that capitalism was already developing in Russia and that this development was historically progressive, even if painful, because it created the proletariat that would eventually overthrow the system.

🏭 The Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class

In 1895, Lenin founded the "Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class" in St. Petersburg, one of the first organizations in Russia to combine Marxist theory with practical work among industrial workers. The organization distributed revolutionary literature, organized strikes, and educated workers about their rights and revolutionary potential. Lenin personally participated in agitating among textile workers and metal workers, gaining valuable experience in revolutionary organization.

The Union's activities quickly attracted police attention, and in December 1895, Lenin was arrested along with other leaders. He spent 14 months in solitary confinement in St. Petersburg's Peter and Paul Fortress, where he continued his theoretical work, writing extensively and even managing to communicate with fellow prisoners through an elaborate system of coded messages written in invisible ink made from milk.

❄️ Siberian Exile and Marriage

In 1897, Lenin was sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia, specifically in the village of Shushenskoye. Far from being a hardship, this period proved intellectually productive. He was allowed to have books sent to him and continued his writing. It was during this exile that he wrote "The Development of Capitalism in Russia" (1899), a comprehensive analysis of Russian economic development that became a foundational text of Russian Marxism.

In 1898, Lenin married Nadezhda Krupskaya, a fellow revolutionary who had been sentenced to exile for her own revolutionary activities. Krupskaya became not only Lenin's life partner but also his closest political collaborator, managing much of his correspondence, organizing his papers, and serving as a crucial link between Lenin and other revolutionaries. Their marriage was based on shared revolutionary commitment rather than romantic passion, though they maintained deep mutual respect and affection throughout their lives.

During his Siberian exile, Lenin also translated key works of Marx and Engels into Russian, helping to make Marxist theory more accessible to Russian revolutionaries. He maintained correspondence with Marxist groups throughout Europe and began developing his ideas about the need for a highly organized, disciplined revolutionary party—ideas that would later culminate in his famous work "What Is To Be Done?"

European Exile and Revolutionary Party Building (1900-1917)

After completing his Siberian exile in 1900, Lenin left Russia for Western Europe, beginning a 17-year period of exile that would see him emerge as one of the most important theorists and organizers of international socialism. His first destination was Munich, where he joined other Russian Marxists in publishing "Iskra" (The Spark), a revolutionary newspaper that aimed to unite scattered Marxist groups throughout the Russian Empire.

📰 Iskra and Revolutionary Journalism

"Iskra" represented Lenin's first systematic attempt to build a centralized revolutionary organization. The newspaper served not just as a source of information but as an organizational tool, with a network of agents and correspondents throughout Russia who distributed the paper and recruited new members. Lenin wrote numerous articles for Iskra, developing his ideas about revolutionary strategy, party organization, and the specific conditions for revolution in Russia.

Through Iskra, Lenin began to articulate his vision of a revolutionary party as a "vanguard of the proletariat"—a highly disciplined organization of professional revolutionaries who would lead the working class in its struggle against capitalism. This concept would later become central to Leninist theory and practice, distinguishing his approach from more democratic socialist movements in Western Europe.

🔀 The Bolshevik-Menshevik Split (1903)

The most significant event of Lenin's early exile period was the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1903, held in Brussels and later London. During this congress, fundamental disagreements emerged over party organization, leading to a historic split between Lenin's faction (the Bolsheviks, meaning "majority") and their opponents (the Mensheviks, meaning "minority").

The split centered on Lenin's insistence on a highly centralized party of professional revolutionaries versus the Menshevik preference for a broader, more open party. Lenin argued in "What Is To Be Done?" (1902) that spontaneous worker movements would inevitably develop only "trade union consciousness" and that revolutionary consciousness had to be brought to the workers from outside by educated revolutionaries. This position was controversial even among Marxists, but Lenin considered it essential for success in the conditions of Tsarist autocracy.

The Bolshevik-Menshevik split would prove decisive in Russian revolutionary history. While the Mensheviks attracted more intellectuals and maintained better relations with Western European socialists, Lenin's Bolsheviks developed a more disciplined organization that would prove crucial during the revolutionary crises of 1905 and 1917.

⚡ The 1905 Revolution and Lessons

The Revolution of 1905, triggered by Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the "Bloody Sunday" massacre, caught most revolutionaries, including Lenin, by surprise. Lenin was in Geneva when the revolution began but quickly returned to Russia in November 1905, using a false passport. Although the 1905 Revolution ultimately failed, it provided crucial lessons that Lenin would apply in 1917.

During 1905, Lenin observed the spontaneous formation of workers' councils (soviets) and became convinced of their revolutionary potential. He also witnessed the crucial role of the military in revolution—uprisings succeeded where soldiers joined workers, and failed where they remained loyal to the Tsar. These observations led him to develop his theory of revolutionary strategy, emphasizing the need to win over soldiers and form alliances with peasants.

The suppression of the 1905 Revolution forced Lenin back into exile, first in Finland and then in Western Europe. The following years (1907-1917) were marked by theoretical development and organizational work, despite frustrating factional disputes within the Bolshevik party and periods of deep pessimism about revolutionary prospects.

📚 Major Theoretical Works

During his long exile, Lenin produced several major theoretical works that would define communist theory and practice. "Materialism and Empirio-criticism" (1908) defended Marxist philosophy against revisionist interpretations. "Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism" (1916) analyzed how capitalism had evolved into a global system of exploitation and argued that imperialism made revolution possible even in less developed countries like Russia.

These theoretical works were not merely academic exercises but were directly connected to Lenin's strategic thinking. His analysis of imperialism, for example, led him to conclude that World War I represented a crisis of capitalism that created revolutionary opportunities. Unlike most European socialists who supported their governments' war efforts, Lenin called for transforming the "imperialist war" into civil war against the ruling classes.

Leading the Bolshevik Revolution 1917

The year 1917 marked the culmination of Lenin's revolutionary career and the vindication of his theoretical and organizational work. When the February Revolution toppled Tsar Nicholas II, Lenin was in Zurich, Switzerland, where he had been living in relative poverty and obscurity. News of the revolution initially filled him with excitement, but he quickly became concerned that other socialist parties might compromise with the bourgeois Provisional Government, missing the opportunity for true revolutionary transformation.

🚂 The Sealed Train Journey

Lenin's return to Russia has become legendary in revolutionary history. Unable to travel through Allied countries due to his anti-war stance, he negotiated passage through Germany in a sealed railway car—a journey that would later be used by his enemies to accuse him of being a German agent. The German government, hoping that Lenin would destabilize Russia and force it out of World War I, facilitated his journey while maintaining the fiction that they had no contact with him.

On April 3, 1917, Lenin arrived at Petrograd's Finland Station to a hero's welcome from workers and soldiers. However, his first speech shocked even his own supporters. While other socialist leaders spoke of cooperation with the Provisional Government and continuing the war effort, Lenin delivered his famous "April Theses," calling for immediate peace, transfer of power to the soviets, and transformation of the "imperialist war" into a revolution against capitalism.

📋 The April Theses: A Revolutionary Program

Lenin's April Theses represented a radical departure from conventional Marxist thinking about revolutionary stages. Orthodox Marxists believed that Russia needed to complete its bourgeois-democratic revolution before attempting socialism. Lenin argued that in the era of imperialism, the proletariat could and must move directly to socialist revolution, even in a backward country like Russia.

The three key slogans of Lenin's revolutionary program became "Peace, Land, Bread"—perfectly calibrated to appeal to war-weary soldiers, land-hungry peasants, and starving workers. "Peace" meant immediate withdrawal from World War I; "Land" meant redistribution of aristocratic estates to peasants; "Bread" meant solving the food crisis plaguing Russian cities. These simple demands masked a sophisticated revolutionary strategy.

Initially, even many Bolsheviks were skeptical of Lenin's radical program. However, as the Provisional Government continued the unpopular war and failed to address economic crisis and land reform, Lenin's position gained support. The failure of the June Offensive and the July Days crisis further discredited the government and vindicated Lenin's analysis that dual power between the Provisional Government and the soviets could not continue indefinitely.

🎭 The Kornilov Affair and Bolshevik Resurgence

In August 1917, General Lavr Kornilov attempted a military coup against the Provisional Government, led by Alexander Kerensky. Although Lenin opposed Kerensky's government, he recognized that Kornilov represented an even greater threat to revolutionary possibilities. The Bolsheviks played a crucial role in organizing armed resistance to Kornilov, despite Lenin himself being in hiding, branded as a German spy by the government.

The defeat of Kornilov's coup attempt dramatically improved the Bolsheviks' position. Workers and soldiers who had previously distrusted them now saw them as defenders of the revolution. Membership in Bolshevik organizations soared, and they began winning majorities in key soviets, including Petrograd and Moscow. Lenin sensed that the revolutionary moment had arrived.

🗓️ Planning the October Revolution

By September 1917, Lenin was convinced that conditions were ripe for armed insurrection. Writing from his hideout in Finland, he bombarded the Bolshevik Central Committee with letters demanding immediate action. His famous declaration that "history will not forgive us if we do not assume power now" reflected his understanding that revolutionary moments are fleeting and must be seized.

Lenin's strategic genius lay in understanding that the Bolsheviks needed to act before the convening of the Constituent Assembly, which might create a legitimate alternative to soviet power. He also recognized the importance of timing the insurrection to coincide with the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, giving the appearance that the soviets, not just the Bolsheviks, were taking power.

The October Revolution (November 7-8, 1917, by the Western calendar) was remarkable for its relatively bloodless nature in Petrograd. Lenin's careful planning, combined with Leon Trotsky's brilliant organization through the Military Revolutionary Committee, allowed the Bolsheviks to seize key points throughout the city with minimal resistance. The capture of the Winter Palace, seat of the Provisional Government, marked the victory of the world's first successful communist revolution.

"Without revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary movement." — Lenin

"The history of all countries shows that the working class, exclusively by its own effort, is able to develop only trade union consciousness." — Lenin, What Is To Be Done?

🏛️ Foundation and Organization of the Soviet State

After the victory of the October Revolution, Lenin faced the enormous challenge of transforming revolutionary theories into governmental reality. As the first Premier of the Soviet Union (Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars), he had to build the world's first socialist state from scratch, often making pragmatic decisions that contradicted his theoretical writings.

The First Decrees

Lenin's first acts as head of government demonstrated his political acumen and commitment to revolutionary promises. The Decree on Peace called for immediate negotiations to end World War I, appealing directly to war-weary soldiers and civilians. The Decree on Land abolished private ownership of land and authorized peasants to seize aristocratic estates, fulfilling centuries-old peasant dreams.

These early decrees were followed by a torrent of revolutionary legislation: nationalization of banks, worker control in factories, separation of church and state, equality of women, and self-determination for ethnic minorities. Many of these measures went far beyond what was possible in Western democracies and established the Soviet Union as a beacon for oppressed peoples worldwide.

The Russian Civil War (1918-1921)

The Russian Civil War tested Lenin's leadership more severely than the revolution itself. Faced with opposition from White armies supported by foreign intervention, regional separatists, anarchists, and even left-wing socialists, Lenin had to make difficult decisions that would define the nature of the Soviet state for decades.

Lenin's approach to the Civil War was characterized by ruthless pragmatism. He authorized the creation of the Cheka (secret police) under Felix Dzerzhinsky to combat counter-revolution. He implemented "War Communism," a harsh economic policy that requisitioned grain from peasants to feed the Red Army and urban workers. He also made the controversial decision to employ former Tsarist officers in the Red Army, despite ideological concerns about their loyalty.

The policy of "Red Terror," officially proclaimed in response to attempts on Lenin's life and other Bolshevik leaders, marked a dark chapter in the early Soviet period. Lenin argued that revolutionary terror was necessary to defend the gains of the revolution against counter-revolutionary violence, but this policy established precedents for authoritarian practices that would later be expanded under Stalin.

The New Economic Policy (NEP)

By 1921, it was clear that War Communism had failed economically and was threatening Bolshevik rule. The Kronstadt Rebellion by sailors who had previously supported the revolution, combined with widespread peasant uprisings, forced Lenin to make a strategic retreat. At the 10th Party Congress in 1921, he announced the New Economic Policy (NEP), a partial return to market mechanisms.

NEP represented Lenin's greatest demonstration of political flexibility. He allowed private trade, small-scale manufacturing, and foreign investment while maintaining state control of "commanding heights" like heavy industry, banking, and foreign trade. Lenin described NEP as "one step backward, two steps forward," acknowledging that building socialism would take longer than initially expected.

The success of NEP in reviving the Soviet economy vindicated Lenin's pragmatic approach, but it also created new problems. The emergence of "NEPmen" (private traders) and prosperous peasants (kulaks) created class divisions that seemed to contradict socialist goals. Lenin's death in 1924 left these contradictions unresolved, contributing to later conflicts under Stalin's leadership.

Building Socialist Institutions

Beyond economic policy, Lenin was instrumental in creating the institutional framework of the Soviet state. The 1918 Constitution established the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, while the 1922 formation of the USSR created a federal structure that granted formal autonomy to different ethnic groups while maintaining Bolshevik control through the Communist Party.

Lenin's approach to nationality policy was more nuanced than often recognized. While committed to eventual assimilation into a socialist culture, he opposed Great Russian chauvinism and insisted on formal equality for minority nationalities. His conflict with Stalin over Georgian policy in his final years reflected his concern that the revolution not reproduce the national oppression of the Tsarist era.

Development of Marxism-Leninism Theory

One of Lenin's most important intellectual achievements was the development and adaptation of Marx's theories to the specific conditions of 20th-century Russia. He proved that socialist revolution was possible not only in advanced industrial countries but also in backward countries. Lenin's theory of the "weakest link of imperialism" paved the way for future revolutions in developing countries.

Lenin emphasized the importance of forming a disciplined and conscious party that could lead the working class. He believed that without such an organization, revolution would not succeed. This idea later became one of the fundamental principles of communism.

Lenin's Global Legacy and Impact

Lenin's influence on world history extended far beyond the borders of the Soviet Union and his era. His ideas and methods inspired revolutions in China, Cuba, Vietnam, and dozens of other countries. The concept of proletarian revolution, disciplined party organization, and anti-imperialist struggle are among the main components of his legacy.

Today, Lenin's name is still associated with revolution, social change, and the struggle for justice. Although there are differences of opinion about evaluating his legacy, his influence on shaping the modern world is undeniable. His works continue to be studied and his ideas are reflected in various social movements.

What Lessons Can We Learn from Lenin Today?

In an era when the world faces economic inequalities, environmental crises, and political instability, Lenin's life and legacy still offer valuable lessons about the nature of power, revolutionary ethics, and the possibility of fundamental change. His unwavering commitment to social transformation, the power of radical ideas, and the importance of continuously challenging the status quo are demonstrated.

For today's activists and thinkers, Lenin's legacy is a call to discover innovative ways toward social justice, considering the real complexities of governing large societies. By studying Lenin's successes and failures, future generations can learn important lessons about the balance between revolutionary fervor and practical governance.

Lenin's Major Works and Intellectual Contributions

Lenin was not only a revolutionary leader but also a prolific writer whose theoretical works fundamentally shaped communist ideology. His collected works span 55 volumes in Russian, covering everything from philosophical treatises to practical guides for revolutionary organization. Understanding his major writings provides insight into the intellectual foundations of the world's first communist state.

"What Is To Be Done?" (1902)

Perhaps Lenin's most influential theoretical work, "What Is To Be Done?" established the organizational principles that would define communist parties worldwide. Written during his European exile, the work argued that revolutionary consciousness could not develop spontaneously among workers but must be brought to them by a disciplined party of professional revolutionaries.

The work's title, borrowed from a novel by Russian radical Nikolai Chernyshevsky, posed the fundamental question of revolutionary strategy. Lenin's answer—the creation of a centralized, conspiratorial organization—contradicted the more democratic approaches favored by European socialists but proved crucial to Bolshevik success in the conditions of Tsarist autocracy.

"Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism" (1916)

Written during World War I, this work provided Lenin's analysis of how capitalism had evolved into a global system dominated by financial capital and characterized by international rivalry for markets, resources, and spheres of influence. Lenin argued that imperialism represented capitalism's final stage, marked by increasing contradictions that would inevitably lead to crisis and revolution.

The work's importance extended far beyond its immediate context. It provided the theoretical justification for revolution in less developed countries and influenced anti-colonial movements throughout the 20th century. Leaders like Ho Chi Minh, Fidel Castro, and Nelson Mandela would later cite Lenin's analysis of imperialism as crucial to their own revolutionary strategies.

"State and Revolution" (1917)

Written in the months before the October Revolution while Lenin was in hiding in Finland, "State and Revolution" outlined his vision of the proletarian state and the transition to communism. The work attempted to reconcile Marx's democratic ideals with the practical necessities of revolutionary governance.

Lenin argued that the bourgeois state apparatus could not simply be taken over but must be "smashed" and replaced with new institutions based on direct worker participation. He envisioned a state modeled on the Paris Commune, where officials would be elected, recallable, and paid no more than ordinary workers. The contrast between this democratic vision and the authoritarian reality of Soviet development became a source of ongoing debate among Marxists.

💰 "The Development of Capitalism in Russia" (1899)

Lenin's first major theoretical work, written during his Siberian exile, provided a comprehensive analysis of Russian economic development that challenged Populist claims about the country's unique path. Using extensive statistical data, Lenin demonstrated that capitalist relations were already developing in Russian agriculture and industry.

The work established Lenin's reputation as a serious Marxist theorist and provided the foundation for his later political strategy. By proving that capitalism was developing in Russia, Lenin argued that the country's working class had revolutionary potential and that socialist revolution was historically possible, even in a predominantly agricultural society.

Lenin's Leadership Style and Revolutionary Methods

Lenin's approach to leadership combined theoretical sophistication with practical ruthlessness, democratic ideals with authoritarian methods, and international vision with Russian patriotism. Understanding his leadership style helps explain both the Bolsheviks' success and the contradictions that would plague the Soviet system.

Centralized Decision-Making

Lenin believed that effective revolutionary leadership required centralized decision-making and strict party discipline. Unlike social democratic leaders who sought consensus through debate and compromise, Lenin insisted on clear hierarchical authority and immediate implementation of decisions. This approach proved crucial during revolutionary crises when rapid action was essential.

However, Lenin's centralized methods also created problems for socialist democracy. Party members who disagreed with official positions faced expulsion, and alternative viewpoints were often suppressed rather than debated. This pattern, established during the underground period, persisted after the revolution and contributed to the emergence of one-party dictatorship.

Strategic Flexibility

One of Lenin's greatest strengths as a leader was his tactical flexibility combined with strategic consistency. He was willing to change tactics dramatically—allying with peasants, employing Tsarist officers, implementing market mechanisms under NEP—while maintaining his ultimate goal of socialist transformation.

This flexibility sometimes confused or frustrated his followers, who expected more ideological consistency. Lenin's famous phrase "one step backward, two steps forward" reflected his understanding that revolutionary progress required temporary retreats and tactical compromises. This approach distinguished him from more doctrinaire Marxists who refused to adapt theory to changing circumstances.

📣 Mass Communication and Propaganda

Lenin understood the crucial importance of communication in revolutionary politics. His newspapers, pamphlets, and speeches were carefully crafted to reach different audiences—workers, peasants, soldiers, intellectuals—with messages tailored to their specific concerns and interests. The Bolshevik success in 1917 owed much to superior propaganda and agitation.

Lenin's approach to propaganda combined emotional appeals with rational arguments, simple slogans with complex theoretical analysis. He insisted that revolutionary ideas must be presented in language that ordinary people could understand while maintaining theoretical sophistication for educated audiences. This dual approach became a hallmark of communist communication strategies.

⚔️ Use of Violence and Terror

Lenin's attitude toward revolutionary violence was complex and evolved over time. Initially influenced by his brother's execution, he rejected individual terrorism in favor of mass revolutionary action. However, the practical demands of revolution and civil war led him to authorize extensive use of state violence against opponents.

The creation of the Cheka (secret police) and implementation of "Red Terror" reflected Lenin's belief that revolutionary violence was necessary to defend socialist gains against counter-revolutionary threats. He argued that the violence of revolution was historically progressive compared to the systemic violence of capitalist exploitation, though this position remained controversial even among socialists.

Economic Policies and Socialist Construction

Lenin's approach to economic policy evolved dramatically from the revolutionary optimism of 1917 to the pragmatic reforms of NEP. His experiences in attempting to build socialism in a backward, war-torn country provided valuable lessons about the challenges of economic transformation.

🏭 War Communism (1918-1921)

War Communism represented Lenin's first attempt to implement socialist economic principles under the extreme conditions of civil war and foreign intervention. The policy included nationalization of large-scale industry, state monopoly of grain trade, prohibition of private commerce, and labor militarization.

While War Communism helped the Bolsheviks survive the civil war by maximizing resource mobilization, it proved economically disastrous. Industrial production collapsed, agricultural output declined dramatically, and black markets flourished despite harsh penalties. The policy's failure forced Lenin to reconsider fundamental assumptions about socialist economic organization.

🔄 The New Economic Policy (1921-1928)

NEP represented Lenin's most significant ideological compromise, allowing private trade, small-scale manufacturing, and foreign investment while maintaining state control of "commanding heights" like heavy industry, banking, and foreign trade. Lenin described NEP as a strategic retreat that would allow the consolidation of socialist power while rebuilding the economy.

The success of NEP in reviving Soviet economic growth vindicated Lenin's pragmatic approach but created new contradictions. The emergence of prosperous private traders (NEPmen) and wealthy peasants (kulaks) seemed to contradict socialist principles of equality. Lenin's death in 1924 left these contradictions unresolved, contributing to later conflicts over economic policy.

🌾 Agricultural Policy and Peasant Relations

Lenin's agricultural policy reflected the complex challenge of building socialism in a predominantly peasant country. His support for peasant land seizures during the revolution contradicted orthodox Marxist preference for large-scale collective agriculture but was essential for maintaining rural support.

Under NEP, Lenin pursued a cautious policy of encouraging agricultural production through market incentives while gradually promoting cooperative forms of organization. He argued that forcing collectivization would alienate the peasantry and threaten Bolshevik power, though he remained committed to eventual socialization of agriculture.

🏗️ Industrialization Strategy

Lenin recognized that successful socialist construction required rapid industrialization to create the material foundation for advanced socialist society. However, he also understood that industrialization in a backward country required careful planning and international cooperation.

His approach emphasized developing heavy industry and modern technology while maintaining worker control and socialist principles. The tension between rapid industrialization and democratic participation would become a central challenge for his successors, ultimately resolved through Stalin's authoritarian methods that contradicted Lenin's more democratic vision.

🎨 Cultural Revolution and Social Transformation

Lenin understood that building socialism required not only economic and political changes but also a fundamental cultural transformation. His approach to cultural policy combined revolutionary idealism with practical recognition of existing conditions, creating tensions that would persist throughout Soviet history.

📚 Education and Literacy

Lenin viewed education as crucial for creating the "new socialist person" and enabling genuine worker participation in governing society. His wife Nadezhda Krupskaya, as People's Commissar of Education, implemented comprehensive reforms designed to eliminate illiteracy and create a new educational system based on Marxist principles.

The Soviet literacy campaign was one of the early regime's greatest successes, dramatically increasing literacy rates among workers and peasants. Lenin insisted that education should combine theoretical knowledge with practical skills, preparing students for productive labor while developing critical thinking abilities. This approach influenced educational policies in socialist countries worldwide.

👩💼 Women's Liberation

Lenin's commitment to women's equality went beyond formal legal rights to encompass fundamental social transformation. The early Soviet legal code granted women equal rights in marriage, divorce, employment, and political participation—advances that were revolutionary for their time.

However, Lenin also recognized that achieving genuine equality required changing deep-seated social attitudes and economic structures. He supported efforts to socialize domestic labor through communal kitchens, childcare facilities, and laundries, though the practical implementation of these ideas proved difficult given the country's poverty and backwardness.

🎭 Art, Literature, and Cultural Expression

Lenin's approach to culture combined support for artistic freedom with recognition of art's social and political significance. He believed that socialist culture should serve the interests of workers and peasants while maintaining high artistic standards, a position that created ongoing tensions between aesthetic and political criteria.

The early Soviet period saw remarkable cultural experimentation, with avant-garde artists, writers, and filmmakers exploring new forms of expression that reflected revolutionary values. Lenin personally supported many of these experiments, though he also insisted that cultural works should be accessible to ordinary people rather than limited to intellectual elites.

⛪ Religion and Atheism

Lenin viewed religion as "the opium of the people" that distracted workers from material struggles and supported existing power structures. However, his approach to religious policy was more nuanced than often recognized, combining ideological opposition with tactical flexibility.

The early Soviet constitution guaranteed freedom of conscience while promoting atheist education. Lenin opposed violent persecution of believers, arguing that religious faith would disappear naturally as socialist education and material progress eliminated the social conditions that created religious needs. This approach distinguished Soviet atheism from the more militant anti-religious policies of some later communist regimes.

🔍 Historical Debates and Modern Interpretations

Lenin's historical significance continues to generate debate among historians, political scientists, and activists worldwide. These debates reflect not only disagreements about historical facts but also fundamental differences in political values and interpretive frameworks.

🤔 The Democratic vs. Authoritarian Lenin

One major debate concerns whether Lenin's authoritarianism was an inevitable result of his theoretical positions or a tactical response to extraordinary circumstances. Some scholars argue that Lenin's concept of the vanguard party inevitably led to dictatorship, while others contend that democratic ideals were central to his vision but were compromised by civil war and economic crisis.

This debate has practical implications for contemporary leftist movements, particularly regarding the relationship between revolutionary leadership and democratic participation. Different interpretations of Lenin's legacy have influenced communist parties, social democratic movements, and various liberation struggles throughout the world.

🌐 Lenin and Anti-Colonial Movements

Lenin's theory of imperialism made him a crucial influence on anti-colonial movements, even though he wrote primarily about European conditions. Leaders of independence movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America found in Lenin's analysis a framework for understanding their struggles against imperial domination.

However, the application of Leninist principles to anti-colonial contexts also raised complex questions about the relationship between national liberation and social revolution, the role of peasant majorities in revolutionary strategy, and the possibilities for socialist development in economically dependent countries.

📊 Economic Legacy and Socialist Development

Economists continue to debate Lenin's contributions to socialist economic theory and practice. His experiments with War Communism and NEP provided valuable lessons about the challenges of economic planning, market mechanisms under socialism, and the relationship between political power and economic organization.

These debates have renewed relevance as contemporary societies grapple with questions about economic inequality, environmental sustainability, and democratic control over economic decisions. Lenin's experiences suggest both the possibilities and limitations of revolutionary approaches to economic transformation.

🕊️ Violence, Revolution, and Political Change

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Lenin's legacy concerns his attitude toward revolutionary violence and its role in political transformation. Critics argue that Lenin's acceptance of violence established precedents for later authoritarian excesses, while supporters contend that revolutionary violence was necessary to overcome systematic oppression and create possibilities for genuine democracy.

This debate extends beyond historical interpretation to contemporary questions about the ethics of political violence, the possibilities for peaceful social transformation, and the conditions under which revolutionary change becomes necessary or justifiable.

👨👩👧 Personal Relationships and Family Dynamics

Behind the public image of the revolutionary leader was a complex individual whose personal relationships profoundly influenced his political development. Lenin's family life, friendships, and intimate relationships reveal dimensions of his character that help explain both his strengths and limitations as a leader.

💕 Marriage to Nadezhda Krupskaya

Lenin's relationship with Nadezhda Krupskaya began during their revolutionary activities in St. Petersburg and developed into one of history's most remarkable political partnerships. Krupskaya was not merely Lenin's wife but a formidable revolutionary in her own right, with expertise in education theory and extensive experience in underground organization.

Their marriage, formalized in Siberian exile in 1898, represented a genuine partnership of equals who shared both personal intimacy and revolutionary commitment. Krupskaya managed much of Lenin's correspondence, edited his writings, and served as an important political advisor throughout their life together. Their relationship demonstrated that revolutionary commitment could coexist with deep personal affection.

However, their childlessness—whether by choice or circumstance—meant that Lenin's emotional energies were focused entirely on political work. Some biographers suggest that this lack of parental experience may have limited his understanding of human nature and contributed to his sometimes harsh treatment of political opponents.

👥 Friendships and Political Relationships

Lenin's capacity for intense friendship was matched by his willingness to break with former allies over political disagreements. His relationship with Julius Martov, his closest friend from university days, exemplified this pattern—their political split over party organization in 1903 ended decades of personal friendship and collaboration.

Similarly, Lenin's friendship with Alexander Bogdanov, a brilliant philosopher and organizational leader, ended when they disagreed over philosophical questions and revolutionary strategy. These patterns suggest that for Lenin, political principles ultimately took precedence over personal loyalty, a characteristic that helped maintain ideological clarity but sometimes damaged important relationships.

Yet Lenin was also capable of remarkable loyalty to those who shared his vision. His relationships with figures like Felix Dzerzhinsky, Anatoly Lunacharsky, and Leon Trotsky demonstrated his ability to work productively with strong personalities when they were united by common purpose.

🎵 Cultural Interests and Personal Habits

Lenin's cultural tastes reflected both his bourgeois upbringing and his revolutionary values. He was a passionate lover of classical music, particularly Beethoven, whose emotional intensity matched his own temperament. He once famously remarked that Beethoven's "Appassionata" sonata moved him so deeply that he couldn't listen to it regularly because it made him want to caress people rather than fight them.

His reading habits were voracious and systematic, encompassing not only Marxist classics but also Russian and European literature, philosophy, and economics. Lenin filled numerous notebooks with detailed comments on his reading, demonstrating the scholarly approach that informed his political analysis.

Despite his intense political commitment, Lenin enjoyed simple pleasures like long walks, cycling, swimming, and hunting. These activities provided necessary respite from political pressures and helped maintain his physical and mental health during the stressful years of revolutionary struggle.

🤝 Relationships with Fellow Revolutionaries

Lenin's interactions with other revolutionary leaders revealed both his political acumen and his personal limitations. His initial alliance with Leon Trotsky during 1917 overcame years of bitter disagreement and demonstrated his ability to prioritize revolutionary success over personal grudges.

However, Lenin's treatment of opponents within the socialist movement was often harsh and unforgiving. His polemics against Menshevik leaders like Martov and international socialists like Karl Kautsky combined legitimate political criticism with personal attacks that made reconciliation difficult.

This pattern extended to relationships within the Bolshevik party, where Lenin's authority was generally accepted but sometimes resented. His "Testament" revealed concerns about Stalin's accumulation of power and recommended his removal as General Secretary, though Lenin's illness prevented him from implementing this recommendation.

🏥 Health Crisis and Final Political Struggles

Lenin's final years were marked by increasing health problems that gradually limited his political activity and created a succession crisis that would profoundly affect Soviet development. His struggle against illness became intertwined with his efforts to address growing problems in the new socialist state.

⚡ First Stroke and Political Concerns

Lenin's first stroke in May 1922 marked the beginning of his decline from active leadership. Even as he struggled with physical limitations, his mind remained sharp, and he became increasingly concerned about bureaucratic degeneration in the Soviet state and the concentration of power in Stalin's hands.

During his periods of recovery, Lenin dictated a series of articles and letters that revealed his growing awareness of systemic problems in Soviet development. These writings, including "Better Fewer, But Better" and his "Testament," represented his final attempts to guide the revolution's future direction.

📝 The Testament and Stalin Question

Lenin's "Testament," dictated in December 1922 and January 1923, provided his final assessment of leading Bolsheviks and their suitability for future leadership. Most significantly, he warned against Stalin's accumulation of power and recommended his removal as General Secretary.

The Testament's suppression after Lenin's death reflected Stalin's growing control over the party apparatus. Lenin's warnings proved prophetic, as Stalin used his organizational position to eliminate rivals and establish personal dictatorship. The document's eventual publication in the West contributed to understanding of early Soviet internal struggles.

🔄 Final Policy Recommendations

Lenin's last writings focused on practical problems of Soviet development, particularly the need to improve governmental efficiency, expand educational opportunities, and maintain the worker-peasant alliance. He advocated gradual cultural development rather than forced transformation and emphasized cooperation with non-communist specialists.

These final recommendations reflected a more moderate approach than Lenin had taken during the revolutionary period. His emphasis on gradual progress and cultural development suggested recognition that building socialism required patience and pragmatic compromise rather than revolutionary enthusiasm alone.

💀 Death and Immediate Legacy

Lenin died on January 21, 1924, at the age of 53, after a series of strokes that gradually incapacitated him. His death created a leadership vacuum that Stalin would exploit to consolidate power, fundamentally altering the direction of Soviet development.

The immediate response to Lenin's death revealed the extent to which his personal authority had held the new state together. Mass mourning demonstrations, the preservation of his body in a mausoleum, and the renaming of Petrograd to Leningrad reflected the population's genuine grief and the leadership's recognition of his symbolic importance.

🔮 Contemporary Relevance and Modern Lessons

Lenin's experiences remain relevant to contemporary discussions about political leadership, social transformation, and the possibilities for fundamental change in established societies. His successes and failures provide valuable lessons for modern movements seeking social justice and democratic transformation.

📱 Leadership in the Digital Age

Lenin's understanding of communication's importance in political organization has new relevance in the digital age. His emphasis on combining theoretical sophistication with accessible messaging parallels contemporary challenges in political communication through social media and digital platforms.

However, Lenin's centralized approach to information control contrasts sharply with the decentralized nature of digital communication. Modern movements must develop new approaches to maintaining ideological coherence while embracing the democratic possibilities of digital technology.

🌍 Globalization and International Strategy

Lenin's analysis of imperialism anticipated many features of contemporary globalization, including the international mobility of capital, increasing inequality between rich and poor countries, and the relationship between economic competition and military conflict.

His emphasis on international solidarity among oppressed peoples remains relevant to contemporary struggles against global inequality and environmental degradation. However, the complexity of modern international relations requires more sophisticated approaches to international cooperation than Lenin's somewhat mechanical application of class analysis to international politics.

🏛️ Democracy and Revolutionary Change

Lenin's tension between democratic ideals and authoritarian methods reflects ongoing debates about the relationship between political means and ends. His experience suggests that revolutionary situations may require extraordinary measures but also demonstrates the dangers of concentrating power in single parties or individuals.

Contemporary movements for social change must grapple with Lenin's legacy while developing new approaches to democratic transformation that avoid the authoritarian tendencies that emerged in the Soviet system. This requires careful attention to institutional design and the cultivation of democratic political culture.

💼 Economic Democracy and Socialist Planning

Lenin's experiments with different approaches to socialist economics—from War Communism to NEP—provide valuable lessons for contemporary discussions about economic democracy, sustainable development, and alternatives to market fundamentalism.

His recognition that socialist construction required both planning and market mechanisms anticipated modern debates about mixed economies and democratic economic governance. However, his focus on state control of the economy must be balanced with contemporary understanding of the importance of civil society and worker participation in economic decision-making.