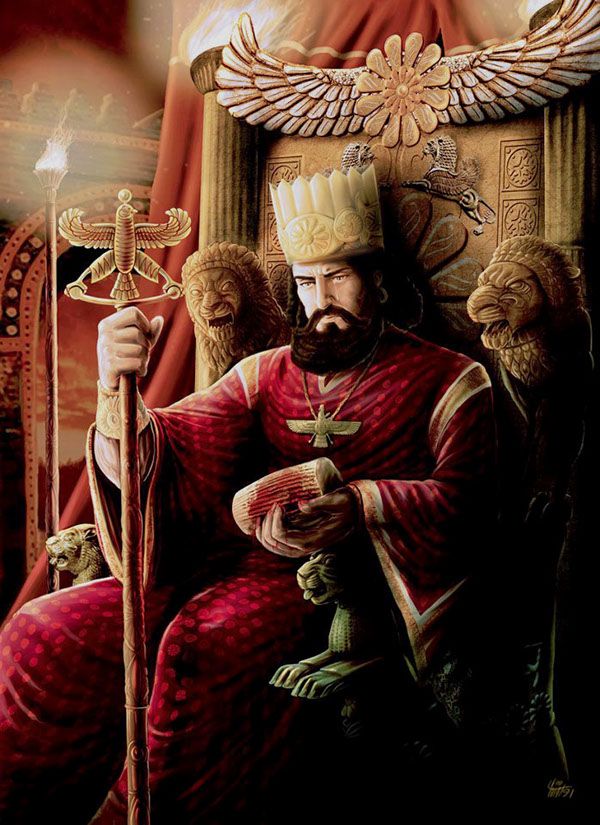

Strategic Leadership Analysis

Xerxes archetypes understand that symbolism fuels logistics. You summon subject nations, stage unforgettable ceremonies, and translate ambition into tangible mega-projects. Morale, narrative, and engineering are woven together so no one forgets the scale of the mission.

Strengths

- Mobilizes multi-nation coalitions through shared ritual

- Balances soft power theatrics with hard infrastructure

- Anticipates morale needs on long campaigns

- Communicates vision with cinematic clarity

- Makes logistical feats feel culturally meaningful

Pressure Points

- Grand displays can mask fragile supply lines

- Slow to pivot once ceremonial plans are in motion

- Risk of insulated echo chambers among courtiers

- May underestimate asymmetric or guerrilla tactics

- Requires grounded operators to translate ambition into detail

Relationship Operating System

You need pragmatic deputies who red-team every plan and surface candid field intelligence.

Deployment Zones

Global events leadership, mega-infrastructure delivery, diplomatic alliances, brand spectacles, transformation coalitions

Leadership Lessons to Apply Today

Pair each spectacle with contingency budgets and review cadences so wow-factor never outruns feasibility.